I have introduced you before to my friend Mark Wright, a Labour activist and Elvis impersonator. He does however have an even bigger musical passion than The King, namely The Boss, and alerted me to an interview Bruce Springsteen has given to The New Yorker, in which he talks about his father’s mental health problems and how these led to problems of his own. I asked Mark if he would like to do a guest blog bringing together one of my favourite subjects – the need for greater openness about mental health and mental illness – with one of his, Bruce Springsteen. Here it is.

If someone were to mention the words ‘depression’ and ‘Bruce Springsteen’ in the same sentence one would perhaps assume that that person was discussing Springsteen’s music in relation to Woody Guthrie and the US economic crash of the 1930s. Not many would associate Bruce Springsteen and depression in the context of mental health.

However, In his recent interview with David Remnick in The New Yorker, Springsteen not only talks openly about his own father’s struggle with depression but of his own sense of self-loathing and fear that he too would succumb to the demons his father fought every day. In Springsteen’s 40 year career this level of candour is unprecedented.

Springsteen famously sings about the small town consequences of economic mismanagement and the human cost that arises when a government or corporation strips away a person’s identity, their pride, their self respect. Critics point out that although he wears the clothing of the working man he himself is as far removed from the working reality as it’s possible to be (a “rich man in a poor man’s shirt” as Springsteen himself wryly observed in his autobiographical song ‘Better Days’ from his 1992 album ‘Lucky Town’).

How, they ask, can a man worth tens of millions realistically connect with the aspirations of the average working man or woman? How can he relate to the feelings of isolation and loneliness that come from a life perceived as disposable not just by the faceless corporation but by the individual themselves? How, they ask, could he possibly understand?

Those of us who are familiar with his work have not had to dig too deeply to find the root cause of many of Springsteen’s stories about the struggles of the working dispossessed. What has distinguished him from previous social commentators such as Woody Guthrie is that for Springsteen the realities of such economic mismanagement have always seemed personal. One only has to listen to songs such as ‘Adam Raised A Cain’, ‘Independence Day’ and ‘Factory’ to understand that much of what Springsteen writes about isn’t so much about the lives of the American everyman, but the life of one man, his father Douglas Springsteen.

Until now the battles the young Bruce Springsteen had with his father have in many ways been mythologized. Some of this was no doubt semi-intentional on behalf of Springsteen himself in his early career. The stories told from the stage in the 70’s and 80’s added an air of romanticism to the story of the teenage outcast who sought refuge in rock and roll having branded his neighbourhood a ‘town full of losers’.

But at the heart of the stories there was always the inescapable fact that they were also true. The young Bruce Springsteen by his own admission wasn’t politically aware in the manner that he is today. He just saw and experienced the consequences of what happened to his dad as time and again he failed to find steady work. That sight scared the young boy from Freehold, New Jersey. Only as he got older did he realize that there was a direct correlation with the depression of his father and the depression of the economy.

After a 40 year career, many may be wondering why Springsteen has chosen this moment to address these issues in such a direct manner? After all, Springsteen’s image has been one of the most closely guarded and controlled of any major artist in modern times. The manner in which he talks so openly and frankly in The New Yorker article about his mental health, as well as that of his father’s struggle with depression and the subsequent impact that had on his own upbringing, is a level of frankness that followers of his music never expected.

But it’s a level of frankness that is to be welcomed wholeheartedly. By being more open with one another about the issues of depression and mental health we can perhaps help each other through that which in previous generations was seldom discussed, let alone understood.

In this time of austerity there are very real, tragic, human consequences being played out in thousands of family kitchens throughout the world. By openly talking about his struggle with depression Springsteen has set an example to others who hopefully will now feel they can do the same rather than sit and suffer in silence.

Scattered throughout the music of Bruce Springsteen there are examples detailing the consequences of just discarding whole swathes of society. We should not ignore such examples no matter where they originate. Telling people they are, in effect, disposable, and that what they have dreamed about for themselves and their families does not matter and can be cast aside this time around can, and will, have direct and measurable consequences for us all. Does anybody believe that the riots of last year in the UK came about as a result of a spontaneous sense of national celebration? No. They were a consequence. Sometimes the consequences are large. Sometimes they manifest in the silent suffering of an individual who feels they have no place in the world any more.

24 hour news channels often report on the economic consequences of recession in purely financial terms. But for every job lost there is a human consequence. For many in our society the legacy of the current economic downturn is not simply a recession of growth but a recession of hope.

It’s important that we look out for one another. And listen.

“I’ll wait for you, and if I should fall behind wait for me.” – Bruce Springsteen ‘If I Should Fall Behind’

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/07/30/120730fa_fact_remnick?currentPage=all

Things can only get worse.

Osborne´s strategy is not working.

Hero of 2010 is now zero. The growth is below zero at -0.7%.

British GDP is still 4.5% below the 2008 peak meaning that the country is technically in depression.

Eurozone is doing better than Britain. Of G20 countries only Britain and Italy are in recession.

GDP fell for a third consecutive quarter.

Recovery has been weaker than from the Great Depression.

Budget discipline is not enough.

BoE´s monetary stimulus is not working. QE programme has so far reached £375bn!

We need PLAN B FOR GROWTH AND JOBS.

OECD, IMF, prominent businessmen etc supported plan A. Sir Mervyn King persuaded Clegg to back it.

Government has no role in economy in Mr. Osborne´s ideology. But private sector is not investing.

George Osborne killed also the consumer confidence by comparing Britain to Greece.

Main purpose of the coalition is to “rescue” the economy.

But borrowing has now increased from 2011.

Output is -0.3% down since 2010! It should have grown 5% since then.

Osborne´s macroeconomic policy of TOUGH FISCAL POLICY plus LOOSE MONETARY POLICY is not working.

He is cutting government´s capital and infrastructure spending causing huge long-term damage.

Deficit reduction plan is off track.

According to PM austerity will now continue for a decade. Treasury has already borrowed £500bn.

If and when Britain loses its AAA credit rating, it will be the final blow for George Osborne´s credibility.

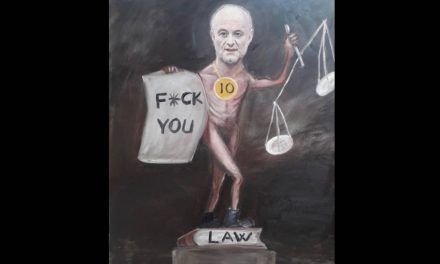

Mr. Osborne must simply go.

I recently was made redundant, I am reasonably secure financially, my partner still has a job, we’ve got no debts, yet whilst expected and financially compensated, the loss of my job was a shock to the system. For those not in such a fortunate position, losing your job is not just a statistic but a real and possibly lasting change with the potential to impact your mental health.

I am familiar with depression, my mother suffered greatly during her life and even though not prone to similar problems, I can see the effects in me of not having my job any more. It’s made clear even when applying for insurance or some other mundane process when you have to tick “unemployed”. The utterly unfeeling attacks on public sector workers makes this worse for those who are trying to do a good job and is entirely ignored by the Govt who wants to “shrink the state”

You’re back then Olli 🙂

How did your project go?

Become a bit of an Arthur Daley, do a bit of buying and selling, via ebay and stuff. It is amazing how much you can make, stuff like what’s on Antiques Roadshow and auction room programmes. Used to do quite a bit of it when younger – cars parts from scrap yards and selling them on was my corner, British Leyland parts. Used to buy cylinder heads for a tenner and used to be able to sell them on for a 500% markup – money for old rope son.

But nothing off a back of a lorry though, honest gov. Times like this is a good time to become entrepreneurial, with people wanting to save money by buying second hand. But ask for advice with NI payments when you decide to go for it and stop claiming the dole. And keep your overheads down – work from your garage at home, if you’ve got one.

Just as good a conversationalist as ever I see! 🙂

Not claiming dole – on a long summer holiday – will look for a “proper job” once the silly season fro jobs is out of the way. Anyway – wasn’t looking for advice, I was commenting on AC’s views about redundancy for many people being a personal issue and not just one number amongst many

E-bay, hmm, well each to their own

Oh come on, you are so paranoid that I was directing my comment totally to you.

You can take what I say, and put it to one side, but others reading might not – have you selfiishly thought that? Other people are trying to get by, unlike you, you selfish wife kept cunt? Heard of Benny Hill in Northertn Italy, in the late sixties? It is symbolic, after WWII, I think, Mozza and itie shite,

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CUcAabeBCEU

Good, yeh? No? oh I give right up, youngsters today, they know shite,,,

Springsteen’s strategy is not working.

Government has no role in economy in Springsteen’s ideology.

Springsteen killed also the consumer confidence by comparing Britain to Greece.

Springsteen’s macroeconomic policy of TOUGH FISCAL POLICY plus LOOSE MONETARY POLICY is not working.

If and when Britain loses its AAA credit rating, it will be the final blow for Springsteen’s credibility.

Springsteen must go.

George Osborne should get his chords right.

Lol. If I was a cynic I would think you were drawing attention to the fact that there is not much connection between Springsteen and the economy Dave. That’s because you are ignoring the fact that Springsteen is part of the Bilderberg group of course, providing them with their signature tune “Born to run” only Cameron modifies it to “I was born to run… things.”

Just eat the right foods, for goodness sake all this BS from pharma and psychiatry make you sick.

Hope is our currency of the future. Now heard of two young guys in Renfrewshire who have committed suicide in the last month. Give us hope – that’s all.