BBC ALBA broadcast a fine one hour documentary last night, about the late lamented Charles Kennedy. Alba, for those who don’t know, is Gaelic for Scotland, which is why I enjoyed watching Scotland’s women’s football team playing Albania a while back, Alb v Alb. Small pleasures …

I was interviewed for the film, and wished my Dad had been alive to see me sub-titled in Gaelic, his native tongue, and one that I never fully mastered as a child growing up in Yorkshire. Judging by the texts and emails and social media messages – especially about my story of Charles saying he had never been to the bottom of Ben Nevis, let alone the top, on account of no constituents living up there – it was clear plenty of people who do not normally watch the Gaelic channel were tuning in. If you missed it, you can catch it on player for the next month.

Most of the media coverage of the film has focused on the way Charles’ SNP opponents exploited his alcoholism in the 2015 campaign that lost him his seat, but thankfully the film as a whole was about much more than that.

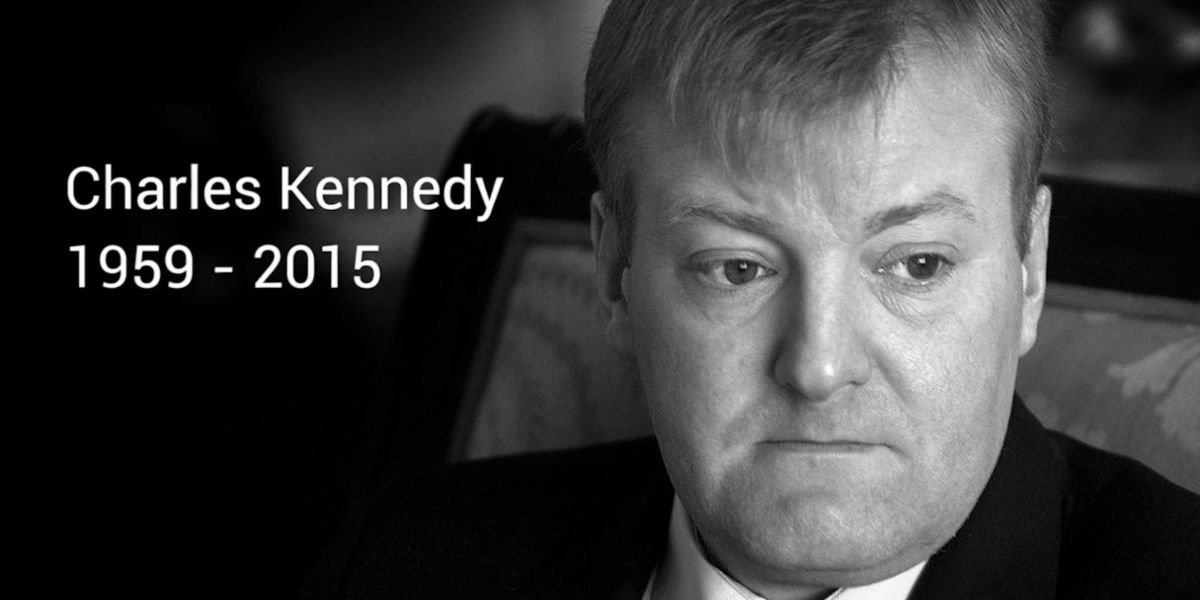

It’s almost six years since he died, not long after the election, yet I can remember it so vividly, both the personal shock and sadness, but also the response of so many who felt the same sense of loss. Last night’s film brought back so vividly why he was so liked and loved.

All in all, it was something of a Charles day, because in the morning I was doing the final, final read through of Volume 8 of my diaries, Rise and Fall of The Olympic Spirit, which is out next month. One of the last tasks was to write the dedication. It reminded me of something friend and colleague Anji Hunter once said to me, ‘make sure I am never your best friend … everyone who gets near you seems to die …’ Death figures large in the dedication. Here, you can have a sneak preview …

“In memory of three people who died in the period covered by this volume:

My wonderful mum, Betty Campbell, 1926–2014

My best friend and colleague, Philip Gould, 1950–2011

My assistant who became a friend, Mark Bennett, 1969–2014

And of three who have died since:

Charles Kennedy, 1959–2015, whose death came

not long after defeat in the 2015 election

Tessa Jowell, 1947–2018, symbol and driver of the Olympic Spirit

Syd Young, 1937–2020, friend, mentor, great man“

Too much death, too much death, and only two of those six, my Mum and Mirror colleague Syd Young, reached what we would define as a reasonably old age. Charles was just 55.

There was a shot of Charles as a young man in a student debating event with Michael Gove. ‘What’s that thing about the Beatles?’ remarked Fiona.

‘Going out in the wrong order?’ I said. And no, I am not saying I wish Michael Gove was dead! I am saying politics could do with a few more like Charles Kennedy in our politics today.

Among the messages this morning was one from journalist Peter MacMahon who said he checked out my website for sight of the obituary I wrote of Charles on the day he died, and suggested I re-post it. So here it is.

“Charles Kennedy was a lovely man, and a highly talented politician. These are the kind of words that always flow when public figures die, often because people feel they have to say those things, and rightly they are flowing thick and fast today as we mourn an important public figure, and a little bit of hypocrisy from political foes is allowed. But when I say that Charles was a lovely man and a talented politician, I mean it with all my heart.

Having heard the news from a friend of Charles who knew he and I spoke and saw each other regularly, and who had found the body yesterday, I finally got to bed at three o’clock this morning, and was awake before 6, feeling shell-shocked and saddened to the core.

Fair to say that most of my friends in politics are on the Labour side but Charles tops the non-Labour ones. I knew him first as a journalist covering his rapid rise, he becoming Parliament’s youngest MP – and one of the most interesting – aged 23, just as I was starting out as a Mirror journalist. He was one of the few politicians with whom I discussed whether they thought I should accept Tony Blair’s approach to work for him, and ‘on balance, all things considered’ (two of his favourite phrases) he felt I should. Then of course later he became Lib Dem leader, and he would ask me in TB’s heyday, half jest, half despair, ‘how on earth do I land a glove on this man?’; but we became especially friendly in more recent years once we were out of the frontline, meeting often, always away from the Commons, to cast interested and sometimes despairing eyes over our respective parties.

But our shared friendship was also built on a shared enemy, and that is alcohol. That Charles struggled with alcohol is no secret to people in Westminster, or in the Highlands constituency he served so well, for so long, until the SNP tide swept away all but one Scottish Lib Dem at the election last month. Perhaps another day, if his family are happy with this, I will write in more detail about the discussions we had over the past few years, and what it was like for someone in the public eye facing the demon drink. It was a part of who he was, and the life he had; the struggles came and went, and went and came, but the great qualities that made Charles who and what he was were always there.

For some years, my family has spent either Easter, or Christmas and New Year, sometimes both, in Charles’ former constituency and he, his wife Sarah before they split up, and their lovely son Donald would always come over, sometimes to stay. I always think one’s own children’s judgement of friends is a good indicator, and my kids, used to politicians in their lives and often seeing straight through them, saw right into Charles for what he was – clever, funny, giving, flawed. My Mum could listen to him all day. ‘I think you’re marvellous on Question Time,’ she would purr about some programme she had remembered from months earlier. She always took his side when I was trying to persuade him he would be a ‘natural on twitter,’ and he felt it was all a bit silly and new fangled. I helped him set up his twitter account. Fair to say he never quite moved that far from his initial assessment.

Mother and children enjoyed his robustness in braving whatever storms were lashing outside ‘to nip out for a wee bit of fresh air,’ otherwise known as a cigarette. Coming as they do from a maniacally exercising family, they appreciated his studied indifference to all forms of heavy exercise. ‘I’ve never actually been to the top of Ben Nevis,’ he said proudly and to great hilarity of the mountain on our doorstep, which had been on his doorstep all his life. They liked the way he advised on where the next long walk should be, ‘but I’ll probably stay and read a book.’

I think they also appreciated that Charles, such a passionate and eloquent opponent of the war in Iraq, was nonetheless unwilling to join those who when it came to their view of Tony Blair or of me, could never see beyond that issue. Charles knew that it was possible to disagree with people without constantly feeling the need to condemn them as lacking in integrity or values; though he was not averse to making a few cracks about historic events down the road in Glencoe.

Even though we knew it was a lost cause, and that Charles would be a Liberal all his life, Philip Gould and I did have an annual dinner time bash at trying to persuade him that deep down he was Labour, and now you have a son at school in London, how about we get you a nice safe Labour seat? Banter political holidays style. It was never going to happen. He was Lochaber to his bones, and a Liberal to his bones.

We were all a bit worried about him after the election. Indeed, ‘is Charles going to be ok?’ was one of the questions Fiona asked me most often during the campaign, and, on the night the exit poll made it clear his safe seat was gone, ‘is Charles ok?’ became an inquiry of a very different nature. Representing the people of Ross, Skye and Lochaber meant so much to him. Last Christmas was the first time he said to me that he felt it was possible he might lose. But we took comfort from the fact that a year earlier, at the same time, we were worrying that the referendum on independence might be lost. We worked on some ideas together and it was partly at his urging that I spent the last few weeks of the campaign in Scotland when – to his astonishment but to his apparent delight – I got on rather well with Danny Alexander, his neighbouring MP.

To be honest, for all the talk of the SNP tide, I did not believe he would lose his seat. He fought very much as Charles, not the Lib Dems and was hilarious about the efforts he intended to go to in resisting any high profile visits. As I know from the time we spend up there, he was hugely popular, but the combination of the toxicity of the Lib Dem brand and the SNP phenomenon proved too powerful a combination.

Going by the chats and text exchanges before and after his election defeat, he seemed to be taking it all philosophically. Before, he took to sending me the William Hill odds on his survival, and a day before the election I got a text saying ‘Not good. Wm Hill has me 3-1 against, SNP odds on, they’re looking unstoppable.’ Then he added: ‘There is always hope … health remains fine.’ Health remains fine – this was a little private code we had, which meant we were not drinking.

A week later, health still fine, we chatted about the elections, and he did sound pretty accepting of what had happened. Here and now is probably not the place to record all his observations about all the various main players of the various main parties north and south, but he said in some ways he was glad to be out of it. I am not totally sure I believed him, but he had plenty of ideas of how he would spend his time, how we would make a living, and most important how he would continue to contribute to political ideas and political life.

Later he texted me ‘fancy starting a new Scottish left-leaning party? I joke not.’ I suggested – though I confess I was joking – that we hold a ‘coalition summit’ at the place we go on holiday. ‘I am up for that – but who do we invite?’

This was to be the agenda for a catch up later this week when he was hoping to get to my brother’s farewell do from Glasgow University, where Charles had been the University Rector for six years, and my brother Donald has been the official University Piper for a lot longer. Charles tried to get me to run for the Rectorship after him – in addition to my brother’s role, my Dad was a Glasgow University vet school graduate – before I gently suggested that with the students voting, this was perhaps one place where his stance on Iraq may have been more helpful to such a campaign than mine.

His kindness to my brother, who has had health struggles of his own, and who Charles met many times at official functions and the like, was another big positive about him in the Campbell household. And I hope his son Donald won’t mind me revealing to the world that as a small boy he loved the bagpipes, and Charles and Sarah had to endure long car journeys with young Donald insisting on playing again and again a CD of my brother Donald’s best solo piping, and I had to play the same tunes on my own pipes once he arrived.

I think of all the memories, that is how and where I will remember Charles, with Sarah and Donald up in one of the most beautiful parts of the world, enjoying each other’s company, enjoying ours as we enjoyed theirs, and being able to talk one minute the future of Europe or the Union, the next where to find the best fish or live local music.

He was great company, sober or drinking. He had a fine political mind and a real commitment to public service. He was not bitter about his ousting as leader and nor, though he disagreed often with what his Party did in coalition with the Tories, did he ever wander down the rentaquote oppositionitis route. He was a man of real talent and real principle.

Despite the occasional blip when the drink interfered, he was a terrific communicator and a fine orator. He spoke fluent human, because he had humanity in every vein and every cell. Above all, he was a doting Dad of his son, whose loss is going to be greater than for any of us, and who will be reminded of his father every time he looks in the mirror and sees his red hair and cheeky smile coming back. And he was a very good friend. I just wish that we, his friends, had been able to help him more, and that he was still with us today, adding a bit of light to an increasingly gloomy political landscape.”

Three years later, I gave the Charles Kennedy Memorial Lecture in Fort William. Here it is, focusing on friendship and mental health, with a bit of Brexit.

And Here is where you can catch the film. Well done BBC Alba and Nina Torrance who managed to tell the story so well, and get so many good interviews done despite lockdown.