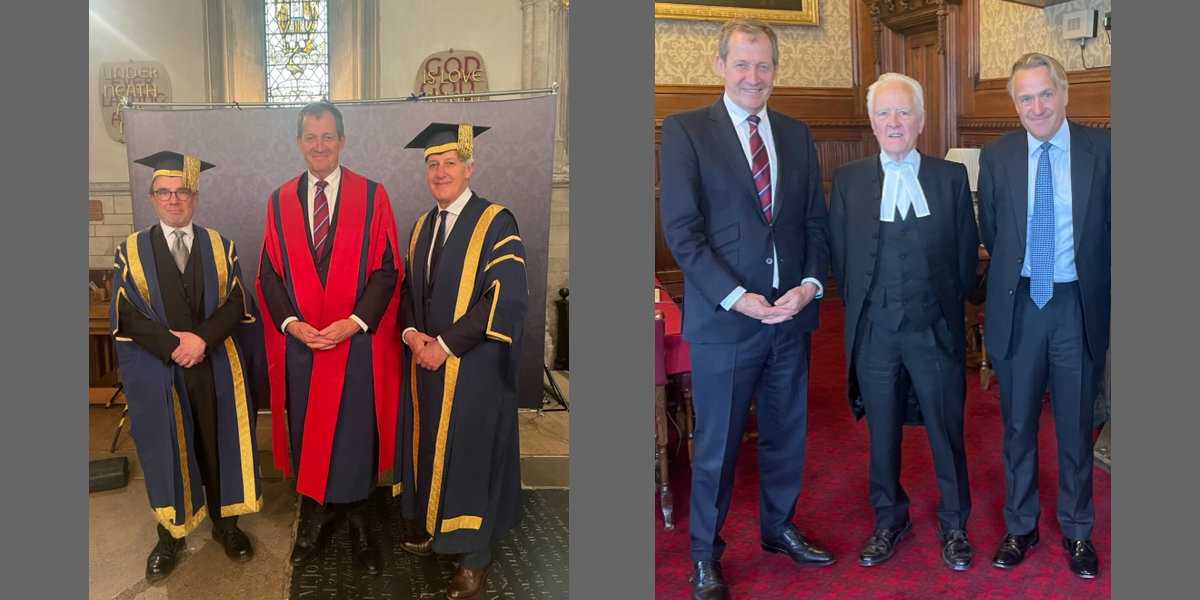

So on the 75th anniversary of the founding of the NHS, what better way to spend it than by being part of a graduation ceremony in which several hundred medical students won the right to put the letters “Dr” before their name; and later, by making a speech on mental health in the House of Lords, as part of Lord Speaker John McFall’s lecture series?

The King’s College ceremony was in the wonderful setting of Southwark Cathedral, and there was something truly joyful about seeing these young men and women, much of whose studies had been done during a pandemic, pick up their scrolls and head off to a life looking after others, as their parents and friends and colleagues cheered them on.

But through the day, as I tracked the voluminous coverage of the NHS birthday celebrations, I barely heard anyone talking about mental health. I had already written the speech for the event in the Lords, which I print below, and one of my themes was that mental health seemed to be returning to the back of the NHS queue. Yesterday’s coverage confirmed me in that fear.

I was at the King’s graduation, because the College was awarding me a Fellowship for the campaigning work I have done over the years in the area of mental health. As Dame Til Wykes, the Professor who heads King’s Mental Health and Psychological Sciences department, read out a hugely flattering citation, she went over many of the key campaign moments of recent years. And it was hard not to feel that for all the progress we believed we had made in recent years, we now seemed to be going backwards again.

Lord McFall, in addition to being an avid listener of The Rest Is Politics, is also a great advocate for mental health and well-being, and it was in listening to the former that he had the idea for last night’s event. On an episode of the podcast last Christmas, I had named Tory MP Charles Walker as one of my Parliamentarians of the Year, because of his openness about his own mental health – OCD – and his campaigning for better awareness and services (not to mention some of his blistering tirades against Boris Johnson).

So there we were, in the splendid Lords’ robing room, the walls dripping with wonderful art, the rows of seats packed out with peers, Parliamentary staff and MPs, including Kevan Jones, one of the first to speak in the Commons about having depression, more than a decade ago, in the same debate in which Charles Walker spoke of his own battle with OCD. .

Charles spoke beautifully of his own condition, but more than that of the importance both of understanding better the complexity of mental illness, but also the need not to “medicalise” the perfectly normal ups and downs of human life, such as sadness and grief. He gave very moving accounts of encounters he had had with people who were struggling. We agreed on the importance of openness, of the need for a more preventative approach, especially focused on children and young people, and on the need for proper investment. We agreed that if we see people in distress, we should seek to help them.

I hope that Charles also posts his speech online. Below is mine. I wish it could have been more positive, but I really do worry we are going backwards, and I have no sense whatever that the current government is remotely focused upon this issue, in the way that some of its predecessors were.

I want to start with the story of two Parliamentarians, both called Charles. Charles Walker, as the Speaker explained, is one of my favourite MPs, of any party. He was one of the first MPs to open up about his mental health challenges, a road that very few have followed since. I can remember the headlines – ‘Four MPs admit to mental health struggles.’ It was considered newsworthy that four had spoken out in that way, in a debate on mental health. Yet that was, and is, a fraction of those who have known mental ill health. We all know that.

My second Charles, Kennedy, knew mental ill health all too well. Depression. Anxiety. Alcoholism. I have known those too. I got lucky. Got arrested in the middle of a psychotic breakdown, hospitalised, began the road to recovery, a road I still tread carefully, by looking after myself better than I once did.

Charles hesitated to get the help he knew he needed. It is a reasonable hesitation, for MPs to worry about what others – opponents, media, constituents – might think. All I would say is that I have never regretted being open, and I know Charles Walker feels the same. Indeed it has been an important part of my recovery, and people have been almost universally understanding and supportive.

I am more than ever convinced, that until people feel they can be as open about their mental health as their physical health, stigma and taboo will remain with us, leading to continuing discrimination, misunderstanding and unnecessary pain, up to and including death, whether through suicide, still the biggest killer of young men, or in Charles’s case through alcoholism.

Four Prime Ministers ago, when Theresa May stood in Downing Street and promised to address “burning injustices,” the fact that she included mental health suggested the issue was rising up the political agenda. Her predecessor David Cameron had also said it was a priority. His Chancellor George Osborne made a big thing of announcing extra funding that I had fought for with Norman Lamb and Andrew Mitchell, as co-founders of the Equality for Mental Health campaign.

However, the signature policy of the Cameron-Osborne years was austerity, which has had a severe impact on mental health services, not least with the return to their traditional place at the back of the NHS queue.

In 2018 then Health Secretary Matt Hancock hosted a Global Mental Health Summit. He invited me to speak at it and, introducing me, said that he felt it was “great that we are talking about mental health more.” I agreed, but said that I felt the talking had been going on long enough, and it was time that governments really started to deliver on that promise, written in the NHS Constitution, of parity between physical and mental health. Let’s be honest, we are a long way from it.

However, as with Mrs May’s speech on taking office, Cameron’s rhetoric, deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg’s support for the (sadly, now defunded) Time to Change campaign, and positive change in volume and tone of media coverage about mental health, it made campaigners hopeful that we were getting somewhere.

Since then, however, not least because of the ABC of Austerity, Brexit and Covid, most in the sector would argue we have gone backwards since the days of New Labour and the early Tory years.

Sometimes campaigns need to be fought and refought before real progress is made. This is one of those fights.

So, how to fight it, how to make the change we need? We need to change the lens through which we look at the issue. First, through that greater openness, key to breaking down stigma and taboo.

Second, by recognising that a preventative approach would end up saving us money as a State. We do not have a mental health service, we have a mental illness service. If I climbed out of the window, jumped, but survived, they would find me a bed at St Thomas’s. But on the many steps from good health to crisis point, all too often the help that might prevent the crisis simply is not there, as the steps towards that crisis evolve. MPs all have stories from their constituencies to back that up. Early intervention, early support, especially in schools, colleges and workplaces, have to be better than waiting for the crisis to come.

That is why the recent statement by Met Police commissioner Sir Mark Rowley, that his officers will no longer answer call-outs related to mental health, unless there is a risk of loss of life, was such a concern. His frustration is understandable, given the shift, from NHS as frontline to police as frontline, which has become normalised in a few years. So third, we must reverse that trend.

I did get Charles to agree to go to a place I know in the Scottish Borders, Castle Craig. He said he was up for it. But by the time I went back to him with dates and rates, he had reasons to put it off – a sick father in need of help, an important speech, a planning meeting for the next election. And so it went on.

The reason I knew about Castle Craig, and felt it would be right for Charles, was because it was where my son Calum sorted out his troubled relationship with alcohol and, an AA regular, he has not touched drink for ten years. But I often wonder what we would have done if we had been unable to pay, as many alcoholics and their families cannot. Fourth, let’s stop that drift to mental health care being a luxury only the well-off can afford, especially as it is likely to be the poor who need it most.

Castle Craig is a place where mainly British alcoholics mingle with mainly Dutch drug addicts, the latter sent there at public expense by a government which understands not just that addiction is an illness, but that those long-term savings can be made for the State if we invest in treating it as such. Some relapse. But many do not. And when those that don’t are able to become healthy productive citizens again, everyone gains from that. I wish our own politicians were as enlightened. Change the lens.

Fifth, the role of employers is vital in this struggle. When I gave the eulogy to my brother Donald at his funeral, I thanked his employer, Glasgow University. Donald, who is the main reason I campaign in this area, had schizophrenia, diagnosed in his early 20s, forcing him to leave the Scots Guards.

To the University, though, which employed him for 27 years, he was never ‘a schizophrenic.’ He was an employee, who had schizophrenia. Big difference. Too many employers define mentally ill staff by their illness in a way they do not when it concerns physical illness. Was I introduced to you tonight as “the asthmatic Alastair Campbell?” No. Has Theresa May ever been introduced as “our diabetic former Prime Minister?”

Sixth, research. Because of the stigma surrounding serious mental illness, it’s at the wrong end of the research queue so that those on a lifetime of anti-psychotics live on average 20 years less than the rest of us. Our Dad was 82 when he died. Donald was 62. Imagine if we knew that the drugs we take for asthma or diabetes shortened our life by 20 years, rather than kept us alive for longer. Would we accept that? Or might we move with the speed we moved to find a Covid vaccine, and find better treatments and better cures?

Seventh, words matter. A plea: never use the phrase “commit suicide” when we talk about someone who ends their own life. We commit sins and crimes. Suicide is neither sin nor, now, crime. It is the ultimate in mental illness.

Let’s stop referring to schizophrenia as a ‘split personality,’ or using the word ‘schizophrenic’ when we mean someone has good moods and bad, or our football team played well in the first half, and badly after half-time. It minimizes. It misunderstands. It stigmatizes.

So let’s change the lens on the way we think, the way we talk and the way we act in relation to mental health; campaign to eradicate discrimination; to end the inequality of access, which means less than a fifth of those who would benefit from talking therapy get it; to understand that long waiting times are even worse when the illness is of the mind; to end disincentives in the system which mean mental health is the service most likely to be cut; to stop people being shunted around the country for treatment; to stop mentally ill kids being locked up in police cells; to accept that prisons are filled with people who should be in hospital not jail; to do that research; to develop that preventative mental HEALTH service; to make the NHS Constitution words on parity between physical and mental health – actually mean something;

But also – if I can move to the final argument in my plea to change the lens – not just to speak up for the mentally ill as people who need support; but to speak up for the mentally ill as, often, major contributors to our life and times.

So eighth, let’s stop seeing mental health purely through the lens of pain and illness. We all have mental health, some days good, some days less so. I agree with Charles that the “one in four” message we have used in campaigning, to show how many of us might have a mental health condition at any time. I prefer “one in one.” We all have mental health, all of us. And even with the illness part, it’s not all bad.

Anything I have achieved in my career I don’t feel that I have done so, as a Telegraph journalist once put it, “despite” a history of mental ill health; but in part because of it. The resilience that comes from building back from breakdown. The ability to deal with setback. A thick skin. Loyalty to others close to me, who have been loyal to me. The energy and creativity that comes from emerging from a depressive episode.

When Charles Kennedy died, there were many who said that had it not been for his drinking, Charles could have been a truly great politician. To me it was like saying Winston Churchill could have been even greater but for his Black Dog and his tendency to drown it in Scotch; Abraham Lincoln would have been even greater without his ‘melancholia’; Bill Clinton would have had a near perfect Presidential reputation had he not had a Kennedy-esque sex drive – that is JFK not Charles.

An American friend of mine, Nassir Ghaemi, has written a book about Martin Luther King, arguing that he became a great leader not despite being a manic-depressive, but because of it. The mania gave him energy and high self-esteem, which contributed to his charisma, and forward-thinking – important in strategy. His depressive side and particularly his understanding of human emotional pain – allowed him to be an exceptional and empathetic team leader.

The reason it’s important to understand all this is that a lot of stigma is still attached to anything that smacks of ‘abnormal’ mental activity. Abnormal does not always mean sick. I don’t want my politicians to be normal; I want them to be special.

Political life is not normal. It is in many ways a laboratory for mental ill health – the hours, the pressures, the separation from family and community, the shocks and setbacks, the volume and nature of issues to deal with, the public hate and toxicity. It would be far better to acknowledge this and work on it, but most leaders just plough on.

Get this: sport is primarily physical, yet you won’t find many top athletes who don’t have psychological support. Politics is primarily mental, yet do politicians really focus on looking after their mental health? They, and the country, would be better off if they did.

So there we are. I hope I may have persuaded some of you to look after yourselves better, and also to get involved in campaigning on this, because it is through campaigning that we can make change. I hope one day we can look back and wonder – did we really accept medications that have barely changed in half a century? Did we really think the mentally ill were more likely to be violent than the general population when in truth they are more likely to be victims of violence? Did we really think it was OK to discriminate in the workplace on the grounds of someone admitting to a mental health problem, as still happens all too often today?

Here is the hope bit on which to end: the same stigma and taboo used to surround cancer. “The Big C.” I remember, as a child, being told by my Mum that our neighbour had cancer. “You mustn’t tell anyone,” she said. That taboo having been stripped away has been a good thing, for those who have cancer, those who treat it, those who raise funds for the fight against it. We need the same stripping away of the taboo surrounding mental health. Only then can we begin to take steps towards making a reality of that promise of parity between mental and physical health, a commitment far from being met, yet which surely must be one of the definitions of a civilised country at ease with itself.

—

After our lectures there was a Q and A session in which all sorts of issues were raised, some of which are reflected in this Evening Standard report of the evening.

Reminds me of my own drift into alcoholism and 2 Hospital Detoxes ,and I found a organisation locally that helped me stay off the Alcohol ,its a hard battle ,as is the fight with your own mental health , i’m now on a straight path with help from friends I made within the group ,if one of us feels like a drink then we support each other ,in staying sober. Loved reading your blog and yes mental health is definitely the poor cousin of physical health ,and I don’t think any of the services are on their way to recovery sadly.