Having just watched Jeremy Corbyn on the Andrew Marr programme, I thought I would post my column in this week’s New European. So if you have already read it, apologies for wasting a few seconds getting you on here; if not, I hope it is of interest. I fear his intervention, though he seemed to me to be trying to indicate a bit more warmth to the idea of a confirmatory ballot on whatever Parliament agrees on Brexit (if it ever does), lacked the clarity needed to halt the leeching of votes to the Liberal Democrats in the European elections. I have been in various parts of the South East over the weekend, and I get the strong impression that these elections are going to see the Brexit Party do well because of deep unhappiness at Mrs May’s Brexit strategy, and the Lib Dems do well in England, and the SNP and Plaid in Scotland and Wales, because of deep unhappiness at Mr Corbyn’s Brexit strategy. Neither can say they have never been warned. Also, Mrs May’s elections campaign launch having come over as a cross between a funeral and a really bad food product launch, and with Labour spending less on the election campaign than the Friends of the Earth, we really are in the midst, so far as the main parties are concerned, of an uncampaign.

Here is my TNE piece.

So, from unleadership which has helped create the mess we are in, we have moved into the writing of its next chapter, the uncampaign.

It is hard not to feel sorry for the main party candidates, men and women who have taken it upon themselves to fight under the Party banner at a time of maximum discontent with their politics, and minimum clarity about the message on the banner.

The Tories still can’t say if they want a hard Brexit or a soft Brexit, the Prime Minister appears to be as resolute as ever in preventing them from answering the question, and the only campaign of any interest to her Cabinet and most of her MPs is the leadership campaign they expect any time soon, already under way with the Cabinet contenders coming over as pygmylogical as they are ill-disciplined.

Labour are a Remain party and a Leave party, depending upon which member of the shadow cabinet has a camera in front of them. There is similar unconstructive unclarity on the question of a second referendum and when shadow justice secretary Richard Burgon said on Radio 4’s Any Questions last week that the Party was ‘in favour of a People’s Vote in some circumstances but not in all circumstances,’ he was greeted by that lethal political commodity – public laughter.

Now, laughter can be a wonderful thing in politics. Check out some of the clips doing the rounds to commemorate the 25thanniversary of the death of former Labour leader John Smith, a master at bringing the House down while making serious political points. But when laughter is the response to what is intended as a serious policy position on the biggest domestic issue of our time, candidates and canvassers have a problem.

How not to feel just a smidgen of sympathy for Tory candidates who somehow have to pretend they want to be there knocking on doors, but they don’t want to mention the name of the Party leader, or, in most cases, say that they support her flagship policy, a withdrawal agreement horse so dead even she no longer seems to flog it with any enthusiasm or expectation of reaching the finishing line; or Labour candidates in the main all aligned on a pro-People’s Vote position, some of whom have been exceptional MEPs and have been strong and clear and honest in the post-referendum debate, but who find themselves constantly having to explain away the divisions and unclarity at the top?

‘If it was a simple case of putting a cross against the name Seb Dance,’ said a neighbour as we discussed our local MEP, ‘I would not hesitate. But we know that if we all do that, he gets elected, great, but then Barry Gardiner or Rebecca Long-Bailey go on the radio and tell me I just voted for their version of Labour’s Brexit plan, and everyone loves Jeremy.’

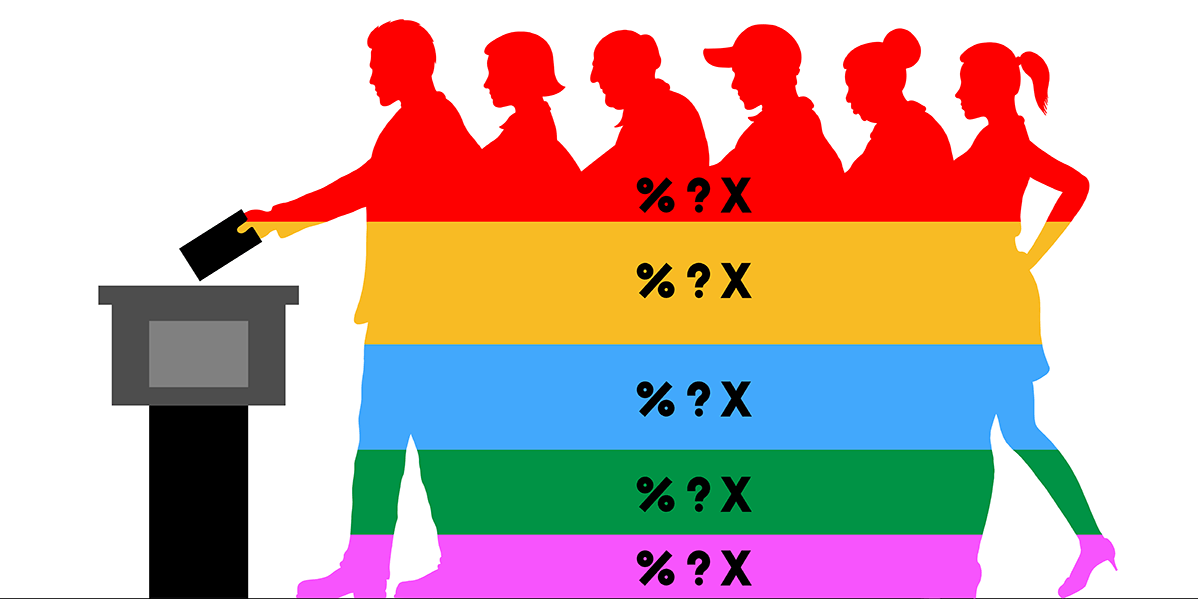

This ‘once bitten, twice shy’ problem is one being reported particularly from those who resent, as I do, that every Tory and Labour vote in Theresa May’s ‘strong and stable’ 2017 election was taken as a vote for Brexit. You will all be used to hearing this one … ‘Eighty percent of people voted for parties which promised to take the UK out of the European Union.’ People, as we will find in these elections, vote (and don’t vote) for all sorts of reasons. I was clear, not least here in this paper, that I was voting and encouraged others to vote Labour as a way of trying to stop Theresa May win a landslide that she (my God how far has she travelled?) confidently expected.

Here is another thing about the 80perent mantra. Neither main party won that election. It baffles me that Labour are expected to deliver on every comma of a manifesto rejected by the country; it further baffles me that a Tory government which lost a majority now seeks to tell the public they must take what both parties offered them, even though both were told by the electorate they were not wanted sufficient for either to be given a clear mandate. The leaders of both seem to be clinging to the wreckage of strategies that have not worked for them.

So on we go with the unleadership and the uncampaign. What was it everyone said, on both sides of the Channel, about not wasting the time granted in the Article 50 extension after we failed to meet the departure deadline? I don’t criticise Mrs May’s capacity to put in the hours, but you would be hard pressed to say that in her belated ‘talks with Labour’ she has displayed any of the urgency, imagination or creativity to reach her intended destination. She has been wasting time, deliberately so. And with Labour locked for several weeks into talks that were quite clearly going nowhere, but on which Jeremy Corbyn in particular did not want to pull the plug, that has further tied them into an uncampaign position.

Of course there is one leader who is doing nothing but campaign, Nigel Farage, though in keeping with the uncampaign theme, his is a campaign without a manifesto, or a clear set of policies on which he can be questioned. But with lots of money coming in from who knows where, with the help and advice of his hero Steve Bannon, with some smart social media work and a mainstream media in the main giving him the easy ride he likes (his whack at the BBC on the Andrew Marr programme was a pre-scripted tantrum straight out of the Trump/Bannon playbook to suggest he is some kind of victim) Farage is making the most of the vacuum left by May and Corbyn. I do not diminish his campaign or communication skills, but it is easier to pull off the trick he is trying to pull – pretending the country voted for no deal when he and virtually every other Leave campaigner said there was no question of leaving without a deal – when the politics and the position of both main parties are so complicated and lacking in clarity, and the leaders of those parties are unable or unwilling to cut through to the public in the way that this current crisis demands.

The smaller parties can do their bit, which they are, and the clarity of their stance is bound to be helping them among those six million who signed a petition to Revoke Article 50, or the million who marched for a People’s Vote. But the Tories and Labour, from the top down, need to do a far better job both of fighting the Farage narrative; and Labour in particular, given the balance of opinion among MPs and members, need to rebut better the frankly ludicrous notion that the very foundations of our democracy would be shaken to the core were we to ask the people to give their consent to whatever Brexit actually means in practice, given all we have learned and experienced since the referendum.

After Saturday’s edition of Any Questions, on Any Answers there was a call from a man in Sheffield, who said he had voted Leave, but he wanted a referendum to vote Remain ‘because they are now saying the opposite of what they said at the time.’ And they are. Farage certainly is. He is being allowed to move from one false narrative to the next. The media has a role to play in challenging him, and should be doing it better. But ultimately, in an election period in particular, it is the job of the parties to engage in and win the big arguments that the election brings to the fore. Good candidates, especially in the European elections, cannot do it alone. It is up to leaders to up their game.

—

Naked plug alert. Nothing to do with Brexit (though the word sneaks its way in) but try to watch my BBC 2 documentary, Me and My Depression, on Tuesday May 21, 9pm. Serious subject, heavy stuff, but as I discovered at a screening on Monday, a few good laughs along the way.

From the author of ‘An Optimist’s Guide to Brexit’:

‘If in these [Euro] elections, most voters back the pro-Brexit parties – either The Brexit Party itself, or UKIP, or indeed the Conservatives and so on, then that is a majority for Brexit – that is really the end of the argument. This should be treated as another referendum on Brexit, and if Nigel Farage’s lot and others aligned with them win this, that that’s it. Over. Argument finished…’

Kudos is due to Andrew Marr for lifting the lid on why the State Broadcaster has been so willing to give the Faragists a free ride over the past few weeks, especially since it’s been revealed by journalists working for less ‘neutral’ organisations that its leader – a self-proclaimed ‘skint’ politician – has received up to £500,000 of undeclared (tho’ presumably, taxable) income and fringe benefits from a benefactor, who is himself currently under criminal investigation.

The BBC may want to keep this particular news story well away from the eyes and ears of the electorate and therefore help ensure that Brexit is ‘over, finished’ and done with, but Marr’s latest on-screen bungle should have precisely the opposite effect.

Perhaps he might consider writing an article titled ‘An Idiot’s Guide to Broadcasting’…

Alastair

Just wanted to thank you for the documentary ‘Me and My Depression’; it was incredibly honest, touching and at times amusing. I nodded along with many of your comments and experiences. I’m one year younger and have lived with depression for well over 30 years. I was a SENCO at a Birmingham Comprehensive until ‘things’ got too much a couple of years ago (“He’s having trouble with his nerves,” would’ve been my parents’ comment) I now tutor kids in care and/or have been permanently excluded. Still that sludge of depression gets to me.

I’m amazed that even with the bouts of depression you’ve performed so well, spoken so brilliantly through it all.

Limk you, my guaranteed time of living in the moment is football – for me it’s my beloved Everton. I loved the footage of you repeating “Get in,” after a Burnley goal.

I’ve been on anti-depressants for most of the last 30 years. However, I sort of slipped into not taking my sertraline tablets last September. A method of ‘dealing’ with depression that wasn’t mentioned is one that’s helped me: ‘Solution Based Hypnotherapy’. I’m not having any sessions at the moment; I’m struggling. That jam jar is something I’m going to give a try.

Many, many thanks.

Gary Williams